Localizing and Sequencing the American Rescue Plan Act: Estimating the Impact in Philadelphia

By Karyn Bruggeman, Colin Higgins and Bruce Katz

August 9, 2021

In April 2021, the Nowak Metro Finance Lab and Accelerator for America released the Federal Investment Guide to the American Rescue Plan (ARPA). The guide broke down The Biden Administration’s COVID relief package from a “bottom-up” perspective: summarizing over 84 individual programs, flowing from 19 federal agencies and through seven different distribution channels. Our goal was to help local leaders identify different sources of ARPA funding and begin strategizing how to put them to productive uses. Ultimately, our hope is that local leaders can put ARPA funds toward driving equity and inclusion in the recovery. ARPA makes great strides in cutting poverty through expanding the federal safety net, and with additional market-making funds in the bill we see a tremendous opportunity for local leaders to build community wealth in the recovery ––especially for neighborhoods and communities hardest-hit by the pandemic.

ARPA's Sequencing Challenge: Funds Arrive in Phases

As we’ve witnessed since March, funds will not flow to every place equally or all-at-once. At the time of press, we are currently in the second phase of ARPA deployment. Short term relief, representing over half of ARPA, has largely been allocated. This included individual relief checks and small business relief, including grants through the Paycheck Protection Program, Restaurant Relief Fund, and Shuttered Venue Operators Grant Fund.

Late summer and early fall 2021 will be the most critical phase of aligning ARPA for maximum impact. This period will require cities and states to plan and apply for competitive grants that open in late 2021 and early 2022.

Programs to Watch Fall 2021 and Winter 2022

- The Economic Development Administration’s newly announced $3 billion competitive grant programs for regional economic development, workforce development, and more, which represent the largest federal investment in economic development, innovation, and competitiveness in decades, and requires multi-faceted applications be submitted by coalitions spanning entire regions. If a single geography secured the maximum award available across four grant programs, they would be eligible for up to $145 million. Cities should be treating the Build Back Better Regional Challenge like the Amazon HQ2 competition, and conducting sprints to complete submissions for fall 2021 and winter 2022 deadlines;

- The to-be-launched $10 billion Capital Projects Fund for broadband expansion run through the Treasury Department;

- The $10 billion State Small Business Credit Program, which states are just getting organized for. Local success of this small business loan program, which anticipates leveraging private capital at a 10:1 ratio to invest in small business growth, expansion, and job creation, amounting to $100 billion in total investments, will depend on the strength of new and existing small business lending intermediaries. The Nowak Lab recently published an explainer on this new round of SSBCI, which includes best practices from the previous round.

- The $24 billion Childcare Stabilization Fund, which requires most states to build brand new systems and structures to distribute an unprecedented amount of funding to childcare providers, and have yet to be dispersed. Most states have yet to set up their programs.

To help local leaders across sectors maximize the transformative effect of ARPA, we’re examining how funds from this complex, multi-faceted bill will impact individual communities. Our hope is that this exercise enables local leaders to orient their thinking and organizations around an inclusive recovery through not just ARPA and subsequent federal investments.

The bottom line: ARPA-alone is the largest federal investment into cities in decades, and it is likely the first act in a multi-act play. Local leaders would do well to get organized and build a targeted strategy around a few big moves. Getting organized now around rescue funds will redound to the benefit of places if recovery funds around infrastructure, innovation, human capital are enacted later this year. Ultimately, cities, local governments and plethora of public, private and civic institutions must get their arms around hundreds of separate programs.

From DC to Philly: A $9.2 Billion Opportunity

In this report, we paint an early portrait of how ARPA funds will flow from the federal to the local level using Drexel’s hometown, Philadelphia, as a case study. Our goal in creating this city profile is to illustrate the bill’s potential impact on a single geography, explore the challenges of tracking and unlocking funds as they flow downward and provide a guide for local leaders to follow when coordinating with for a strategic and aligned deployment of ARPA funds across silos.

The big takeaway: The whole funding pie is much larger than what units of local governments are receiving through the Treasury Department’s much discussed State and Local Fiscal Recovery Fund (SLFRF). While flexible SLFRF funds to state, county, and city governments have received the most attention, a strategic, effective recovery requires coordination with the dozens of public and private entities set to receive ARPA funds in any given locality. Philadelphia alone is on tap to benefit from over $9.2 billion in ARPA funds, only $1.4 billion of which will be delivered as SLFRF fiscal relief funds to the City of Philadelphia. In our analysis of 60 different ARPA funded programs, it becomes clear that dozens of public agencies and major institutions, thousands of businesses, and hundreds of thousands of households across the city will receive funds from this one relief bill.

Harnessing the whole of this federal investment for a big impact requires a strategic organizing effort. Trying to coordinate the totality of ARPA on the local level, while possible, is not reasonable for an individual institution. It requires tracking a dizzying array of timelines, recipients, and regulations. Fortunately, it is also not necessary. Local leaders need to make a targeted efforts to align a few key organizations to achieve shared goals. Focusing on which institutions and what goals are where strategy and the organization matter.

Strategic organizing is necessary. If local leaders do not understand the full spread of where relief funds are going, they open themselves to a series of downside risks. These include: wasting the most flexible funds on duplicative efforts, missing opportunities to bring in private or philanthropic capital to compliment specific sources of relief funds, not leveraging disparate investments that flow to the same disadvantaged communities, or not drawing down on their fair share of federal relief by missing out on competitive funding opportunities.

Key Questions for Local Leaders

In tracking the flow of ARPA funds ––and future federal spending bill–– to your city, key questions to consider include:

- Which entities in your city are receiving ARPA funds? If programs require applications, who must apply, and by when?

- How much are they receiving?

- How do ARPA funds fit into key policy and revitalization goals? Which entities have shared or overlapping policy goals?

- What are the specific eligibility rules governing fund usage (and when will they be finalized)?

- Where are ARPA funds suited to solve immediate problems? And where are they best suited to achieve longer-term goals?

- How can we foster collaboration across silos when dozens of different entities are receiving supplemental funds?

- How can local leaders leverage private and philanthropic investments to amplify ARPA funds and multiply their impact in distressed communities?

Tracking the Flow of ARPA Dollars in Philadelphia

Across the country, the $350 billion in SLFRF funds issued by the Treasury Department are getting the lions’ share of public attention. This is precisely because they are a new and rare infusion of relatively flexible funding. In Philadelphia, these flexible funds amount to $1.4 billion arriving in two tranches, only 15 percent of all funds.

Focusing only on the most flexible funds gives an incomplete view. In reality, Philadelphia and its residents are on tap to receive over $9.2 billion in ARPA funds. Below, we outline estimates of Philadelphia-specific ARPA awards across 60 funding streams. These estimates paint a more complete picture of how ARPA funds are flowing, and it provides a guide for which kinds of city organizations city leadership should connect with and collaborate with on the deployment of ARPA funds.

Philadelphia Entities Receiving Funds

A short list of local entities receiving funds in Philadelphia alone includes:

- School District of Philadelphia,

- Philadelphia Department of Public Health,

- Philadelphia Housing Authority,

- Southeast Pennsylvania Transit Authority (SEPTA),

- 1,600 licensed childcare facilities,

- 82 individual charter schools,

- 32 housing counseling intermediaries,

- 14 colleges and universities,

- 12 community health centers,

- 2 health center controlled networks,

- and over one million individuals.

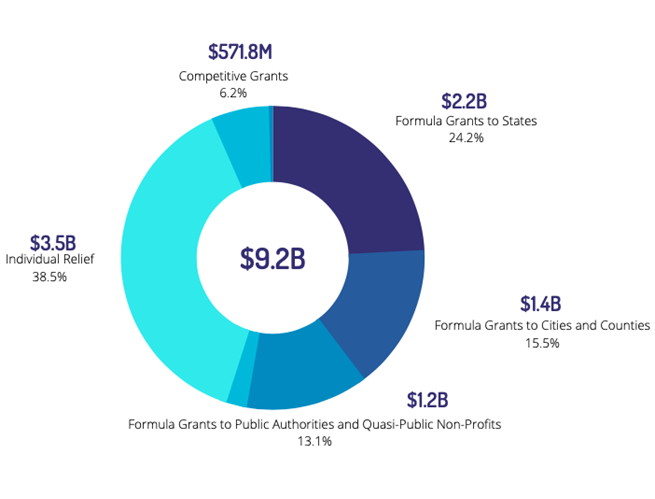

Individual funds made up a significant proportion of ARPA early stages, including the individual $1,400 checks delivered in 2021 and supplemental unemployment benefits scheduled to run out in September 2021. While those benefits dwarf other investments, the sheer scale of ARPA funding merits an examination of funds flowing through all channels, visualized below.

Philadelphia ARPA Funds by Distribution Channel

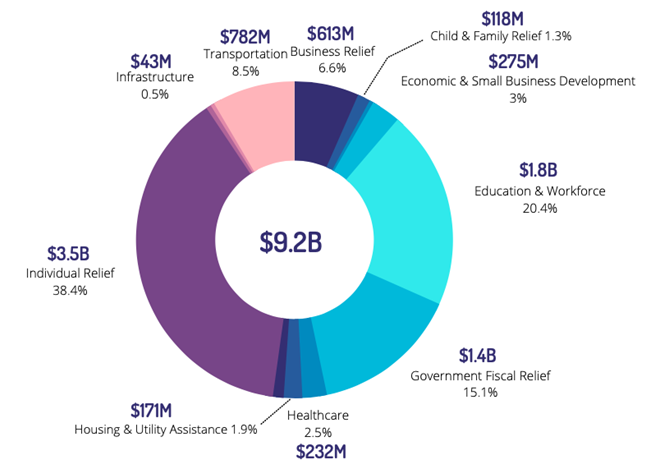

Philadelphia ARPA Funds by Category of Funding

Key Takeaways for All Cities

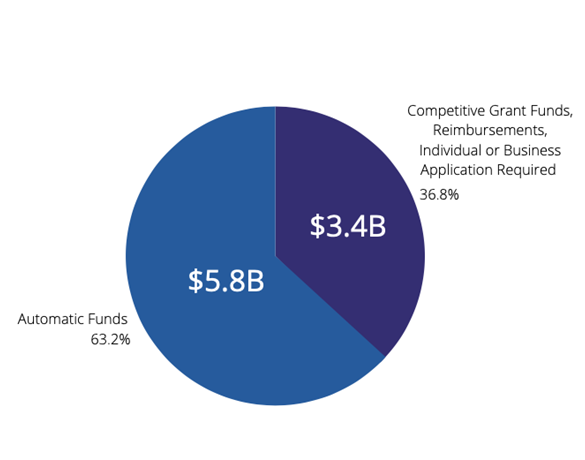

1.) Flexible Funds are Only One Component: The SLFRF funds going to cities and municipalities are notable for their relative flexibility, but they make up only 15 percent of all ARPA funds flowing to Philadelphia, and the same is generally true for other cities. The graphic above puts Philadelphia’s flexible funds, labeled “Government Fiscal Relief,” in context. The pie chart below shows how only some funding streams are arriving automatically while up to 37 percent, totaling $3.4 billion available, requires effort to draw down and secure.

Of those competitive funds, some must be unlocked by application, whether it’s an individual claiming tax credits through filing their taxes, a small business applying for grants or loans, or non-profits or local governments submitting applications for competitive funds, as well as public funds that require involved application processes to unlock. Many of these funds ––especially those intended for individual relief–– have already been expended (or are currently open for application). In the Methodology document, individual programs are distinguished by which category they fall under.

Philadelphia ARPA Funds: What’s Arriving Automatically vs. What Requires Effort

2.) Diffuse Distribution Requires Tracking and Coordination Across Silos: We have written that America is a “perpendicular nation” with federal silos operating vertically and local actors organizing horizontally. Given the breadth and depth of ARPA funded programs this point is key. Relatively flexible SLFRF funds will be best spent supplementally ––as the axis that translates from federal silos to horizontal actions. Given emerging eligibility criteria, we see these funds best used on transformative projects, especially in low-income Qualified Census Tracts, rather than being spent in a manner that is duplicative of other relief efforts with dedicated funds. These funds can also be more clearly tracked by City Hall than other funds (making tracking and evaluation imperative). Identifying who’s receiving what and determining what is or is not duplicative requires creating a profile for your city similar to what we’ve created here for Philadelphia.

3.) Scale Competitive Applications to Size: Competitive funds are the most challenging to estimate for local cities, given that any actual award depends on the amount potential grantee applies for. However, quick calculations of what your city could be eligible for based on their proportion of the population can help ensure cities are applying for big enough grants, given the huge amount of funding made available by ARPA.

4.) Sequencing is Key and Requires Broader Coordination: Not all ARPA funds will flow at once. Some have already been completely spent; others have been minimally allocated. It is crucial to develop a strategic sequencing approach that matches three components: (1) timing; (2) eligible uses, and (3) the receiving entity. This is not a small amount of work for already over-worked City Halls that have been functioning on crisis-response mode for the past 18 months. That’s why we have been working with key first-mover cities, including Philadelphia, to establish Stimulus Command Centers that bring the private and public sectors together to determine key impactful investments and leverage their impact over time. More on sequencing can be found in section III.

A Programmatic Break-Down by Distribution Channel in Philadelphia

To create this profile of Philadelphia, we aimed to be both comprehensive and realistic about the limitations of making estimates for some programs. The charts below map estimates of how funds will flow by seven distribution channels. Hard numbers that have been publicly reported are in regular text. Estimates that have been calculated by Nowak Lab staff are in italics, with special characters to note what kind of estimate was made.

For a deeper look into how we made estimates for individual programs, see Appendix B and the supplemental methodology document.

|

Formula Grants to State and Territories

|

|

Fed. Agency

|

ARPA Program

|

Philadelphia Recipients

|

Local Estimate

|

|

Educ.

|

Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund (ESSER): K-12

|

School District of Philadelphia

|

$1.114 billion

|

|

Educ.

|

ESSER: K-12 Public Charter Schools

|

82 charter school local education agencies (LEAs) located in Philadelphia

|

$466.3 million

|

|

Educ.

|

ESSER: IUs, CTCs, PRRIs, APSs, A-TSI Schools

|

Philadelphia IU 26, Philadelphia AVTS,

School District of Philadelphia A-TSI, educational programs to delinquent, neglected, and at-risk youth, private schools

|

$16.3 million

|

|

Educ.

|

K-12 Homeless Children and Youth Program

|

School District of Philadelphia, charter school LEAs

|

$12.9 million*

|

|

Educ.

|

Emergency Assistance to Non-Public Schools (EANS)

|

Private K-12 schools

|

$18.7 million*

|

|

Educ.

|

State Special Ed.

|

School District of Philadelphia, others

|

$12.8 million*

|

|

HHS

|

Child Care Stabilization Funds

|

1,628 licensed childcare centers and providers in Philadelphia County as of April 2021

|

$170 million++

|

|

HHS

|

Child Care & Development Block Grant

|

1,628+ licensed childcare centers and providers in Philadelphia County as of April 2021

|

$118 million++

|

|

Treasury

|

Emergency Rental Assistance Program (ERAP)

|

City of Philadelphia

|

$37.3 million

|

|

Treasury

|

Homeowner Assistance

|

Individual homeowners

|

$43 million*

|

|

HHS

|

Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP)

|

Individuals

|

$36.6 million*

|

|

HHS

|

Low Income Home Water Assistance Program (LIHWAP)

|

Individuals

|

$2.3 million*

|

|

Treasury

|

Capital Projects Fund

|

Broadband expansion projects (TBA)

|

$34.3 million*

|

|

HHS

|

COVID Vaccine Activities

|

City of Philadelphia, Community Health Centers, vaccine providers

|

$14.3 million

|

|

USDA

|

Pandemic EBT Youth Nutrition

|

80% of School District of Philadelphia students qualify, equaling ~ 162,300 students

|

$66.4 million**

|

|

USDA

|

SNAP Value Increase

|

481,000+ SNAP enrolled Philadelphians

|

$36 million**

|

|

USDA

|

WIC Value Increase

|

36,176+ WIC enrolled Philadelphians

|

$3.62 million**

|

|

HHS

|

Support for Older Americans

|

Various programs

|

$7.38 million*

|

|

HHS

|

Pandemic Emergency Assistance Fund

|

Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) recipients

|

$15.3 million**

|

|

HHS

|

Family Violence Prevention Services (FVPSA) Funds

|

Pennsylvania received $4.5 million in FVPSA supplemental funds and $299,107 for their State Domestic Violence Coalition (SDVC)

|

$590,000*

|

|

HHS

|

Child Abuse Prevention & Treatment

|

Non-profits, CBOs, public health organizations, state and local governments

|

$1.5 million*

|

|

HHS

|

Community Mental Health Block Grant

|

Non-profits, CBOs, public health organizations, state and local governments

|

$5.7 million*

|

|

HHS

|

Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment Block Grant

|

Non-profits, CBOs, public health organizations, state and local governments

|

$5.84 million*

|

|

Total

|

$2.239 billion

|

|

Formula Grants to Cities and Counties

|

|

Fed. Agency

|

ARPA Fund

|

Philadelphia Recipients

|

Local Estimate

|

|

Treasury

|

Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds

|

City of Philadelphia

|

$1.39 billion

|

|

HUD

|

HUD Homelessness Assistance (HOME Investment Partnerships Program)

|

City of Philadelphia

|

$42 million

|

|

Total

|

$1.432 billion

|

|

Formula Grants to Public Authorities & Quasi-Public Non-Profits

|

|

Fed. Agency

|

ARPA Fund

|

Philadelphia Recipients

|

Local Estimate

|

|

CDC

|

COVID Lab Capacity for Testing and Tracing, Lab Capacity for Genomic Sequencing, COVID Vaccine Preparedness, Crisis Cooperative Agreement: Public Health Workforce Supplemental Funding, Disease Intervention Specialist workforce, Emerging Infectious Diseases Detection and Mitigation

|

City of Philadelphia & School District of Philadelphia, Dept. of Public Health, others

|

$94.29 million

|

|

DOT

|

Federal Transit Administration Grants

|

SEPTA

Senior Mobility Grants

|

$667 million

$898,365

|

|

DOT

|

Airport Relief

|

Philadelphia International Airport, Northeast Philadelphia Airport

|

$115 million

|

|

DoEd

|

Higher Ed Grants (HEERF III)

|

University of Pennsylvania, Drexel University, Temple University, La Salle University, St. Joseph’s University, Chestnut Hill College, Moore College of Art and Design, University of the Sciences, University of the Arts, Community College of Philadelphia, Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine, Curtis Institute of Music, Holy Family University, Peirce College

|

$239.3 million

|

|

HHS

|

HHS Community Health Center Support

|

Covenant House, Delaware Valley Community Health, Esperanza Health Center, Greater Philadelphia Health Action, Philadelphia Fight, City of Philadelphia, Project HOME, Public Health Management Corporation, Quality Community Health Care, Resources for Human Development, Sayre Health Center, Spectrum Health Services

|

$56.6 million

|

|

HHS

|

HHS Community Health Center Support: Construction and Renovation Projects

|

Covenant House, Delaware Valley Community Health, Esperanza Health Center, Greater Philadelphia Health Action, Philadelphia Fight, City of Philadelphia, Project HOME, Public Health Management Corporation, Quality Community Health Care, Resources for Human Development, Sayre Health Center, Spectrum Health Services

|

$9.1 million++

|

|

HHS

|

HHS Community Health Center Support: Health Center LALs

|

City of Philadelphia

|

$11.7 million++

|

|

HHS

|

HHS Community Health Center Support: Health Center Controlled Networks Awards

|

The Health Federation of Philadelphia, Public Health Management Corporation

|

$357,500++

|

|

HUD

|

Emergency Housing Vouchers

|

Philadelphia Housing Authority, 863 vouchers

|

$10 million

|

|

HUD

|

Housing Counseling

|

Eligible HUD-approved intermediaries, state housing finance agencies, and NeighborWorks network organizations will be invited to apply for funds starting June 2, including

32 HUD-approved Housing Counseling Agencies in Philadelphia

|

$480,000*

|

|

HHS

|

Head Start

|

117+ Head Start centers in Philadelphia

|

$4.2 million*

|

|

IMLS

|

Museum & Library Relief

|

Free Library of Philadelphia

|

$578,000*

|

|

CPB

|

Corporation for Public Broadcasting Relief Funds

|

WHYY-TV, WHYY-FM, WXPN-FM

|

$846,885

|

|

Total

|

$1.21 billion

|

|

Capital Products

|

|

|

ARPA Fund

|

Philadelphia Recipients

|

Local Estimate

|

|

Treasury

|

State Small Business Credit Initiative (SSBCI)

|

Individual businesses

|

$125 million++

|

|

SBA

|

Targeted Economic Injury Disaster Loan Advance

|

Individual businesses

|

$52.5 million*

|

|

SBA

|

Paycheck Protection Program

|

Individual businesses

|

$27 million+

|

|

Total

|

$204.5 million

|

|

Individual Relief

|

|

Fed. Agency

|

ARPA Fund

|

Eligible Applicants

|

Local Estimate

|

|

Treasury

|

Individual Payments

|

Over 1 million individuals

|

$1.4 billion

|

|

IRS

|

Child Tax Credit

|

Estimated 300,000 newly eligible children

|

$900 million**

|

|

IRS

|

Earned Income Tax Credit

|

Estimated 146,000 newly eligible workers without children

|

$114 million**

|

|

DOL

|

Unemployment Ins.

|

74,800 Philadelphians were unemployed in March 2021

|

$1.15 billion**

|

|

Total

|

$3.56 billion

|

|

Competitive Grants

|

|

Fed. Agency

|

ARPA Fund

|

Eligible Applicants

|

Local Estimate

|

|

SBA

|

Restaurant Revitalization Fund

|

Over 730 individual Philadelphia businesses received grants, according to SBA data, out of over 6,000 dining establishments in the city

|

$279 million

|

|

SBA

|

Shuttered Venues Fund (Including full $16 billion from CCRRSA + ARPA)

|

66 Philadelphia venues were approved for grants as of July 30, 2021, worth $82.5 million, according to SBA data

|

$85.2 million*

|

|

FCC

|

E-Rate Grants for Emergency Educational Connections

|

Libraries and schools

|

$34 million*

|

|

Commerce

|

EDA American Rescue Plan Grants

Build Back Better Challenge

Good Jobs Challenge

Economic Adjustment Assistance

Travel, Tourism, and Outdoor Recreation

Indigenous Communities

Coal Communities Commitment

Statewide Planning, Research, and Networks

|

State and local governments, non-profits, private sector entities aligned with public sector entities, higher education institutions, Economic Development Districts (EDDs)

|

$145 million++

|

|

HHS

|

COVID-19 Expanded Genomic Sequencing

|

New Centers of Excellence in Genomic Sequencing, bioinformatics infrastructure projects

|

$1.6 million*

|

|

HHS

|

Pediatric Mental Health Care Access – New Area Expansion Grants

|

States or political subdivisions of states not currently funded under HRSA-18-122 and HRSA-19-096

|

$2.25 million++

|

|

HHS

|

HHS Public Health Workforce Expansion

|

Community health centers, non-profits, public health departments, academic institutions, education providers

|

$12.5 million

|

|

NSF

|

COVID Related R&D

|

Research and education projects in science and engineering related to COVID-19

|

$2 million*

|

|

HHS

|

Expansion Grants for Community Behavioral Health Centers

|

|

$2 million*

|

|

FEMA

|

Emergency Food and Shelter Program

|

|

$1.9 million*

|

|

FEMA

|

Firefighter Grants

|

Local fire departments

|

$1.4 million*

|

|

SBA

|

Community Navigator Pilot

|

Non-profits, economic development organizations, county, state, or city governments, SBA Resource Partners,Small Business Development Centers (SBDCs), Women’s Business Centers, SCORE, Veterans Business Outreach Centers (VBOCs),

CommunityDevelopment Financial Institutions, and non-profit colleges and universities

|

$5 million++

|

|

NIST

|

COVID Related Manufacturing R&D

|

Manufacturing Extension Partnership (MEP) Centers, Manufacturing USA programs, other NIST-funded programs

|

$720,000*

|

|

NEA

|

COVID Arts Relief

|

Arts organizations

|

$670,000*

|

|

NEH

|

COVID Humanities Relief

|

Museums, libraries and archives, historic sites, independent research institutions, academic presses, professional organizations, colleges and universities

|

$670,000*

|

|

EPA

|

EPA Grants for Pollution and COVID mitigation in Low-Income Communities

|

States, cities, and county government eligible for Air Quality Monitoring grants or Environmental Justice Fund grants

|

$480,000*

|

|

HHS

|

Administration for Children and Families: New Competitive Grant Program to Support Community-Based Culturally Specific Activities for Survivors of Sexual Assault ($49.5 million)

|

Non-profits, others to be announced

|

$23,700*

|

|

HHS

|

Administration for Children and Families: New Competitive Grant Program to Help Rape Crisis Centers Transition to a Virtual Services Model ($198 million)

|

Rape crisis centers

|

$95,000*

|

|

Total

|

$571.8million

|

|

Reimbursement & Public Procurement

|

|

ARPA Fund (National Amount)

|

Philadelphia Recipients

|

Local Estimate

|

|

FEMA Disaster Relief ($50 billion)

|

City of Philadelphia

|

$34.3 million

|

|

Total

|

$34.3 million

|

The Road Ahead: ARPA's Sequencing Challenges, Revisited

ARPA will not arrive all at once. While most has already arrived or been obligated, much of the remainder will be allocated in tranches with a multi-year tail on spending. This gives local leaders time to plan. Looking ahead, it will be increasingly important to conceptualize the programs funded by the bill based on when funds become locally available and when they expire. This will influence what public, private, and civic leaders should mobilize around in the present, over the next six months, and over the next year and beyond. To help, we created the ARPA Timing & Sequencing Memo.

The Mid-Term: A Focus on Competitive Grants

At the time of press, we are currently in the second phase of ARPA deployment. Short term relief (representing over half of ARPA) has largely been allocated. The mid-term is the most crucial phase of aligning ARPA for maximum impact. It requires cities and states to plan and apply for competitive grants open in 2021 and 2022. The central challenge during this phase for city halls will likely be grant-writing capacity, and coordination with the various local city departments and public authorities eligible to apply. Application windows for ARPA-funded competitive grants open-up on a staggered schedule. Cities must track notices of funding availabilities (NOFAs) and encourage eligible city agencies, community partners, research institutes, and businesses to apply, particularly to ensure those same entities don’t try to draw from limited flexible city funds for projects that could be funded through competitive grants. As the case of Philly highlights above, if cities do not act they risk leaving a significant portion of relief on the sidelines or spending SLFRF funds in a duplicative manner.

Charts outlining the key competitive federal grants included in ARPA and examples of ARPA-funded grants listed on Grants.gov as of May 2021 can be found here. Given that ARPA federal funds are flowing through over 84 programs, tracking funding opportunities can be a daunting task.

Three General Rules Apply

Rule 1: Timing varies & sub-grants are the norm

Competitive ARPA funding sources are primarily being offered as supplements for pre-existing federal grant programs, meaning the application windows for individual programs will vary. Funds are not necessarily going to open-up for applications all at once and are instead likely to be broken down into smaller grant opportunities with specific sub-areas of focus. This can be leveraged to local leaders’ advantage if you know your priorities.

Example: ARPA included $100 million in supplemental funds for various Environmental Protection Agency grant programs. As of May 26, 2021, applications were open for $16.5 million worth of those funds across two different grant programs, with more announcements to follow. $9.2 million worth of funds were open through the Environmental Justice Collaborative Problem Solving Grants (EJCPS) program, and $7.3 million were open through the Environmental Justice Small Grants (EJSG) program.

Rule 2: Formula & competitive funds are often combined

Some ARPA funds will be offered as a mix of formula and competitive grants, rather than exclusively as formula grants. This is particularly true for funds focusing on public health innovation and the response to COVID-19 –– disbursed through the CDC and HHS–– which we previously identified as formula grants to public authorities in the Federal Investment Guide. That said, some grants are competitive only in the perfunctory sense; that is eligible entities must secure set amounts through an application process.

Example: ARPA included $7.6 billion in HHS funds to support community health centers, which we categorized as formula funds in the Federal Investment Guide. Of that, $6 billion of the funds were awarded by formula to community health centers nationwide, $1 billion is being awarded for health center construction and capital improvements on an application-only basis, and an additional $150 million is open to health center look-alikes (LALs) on an application-only basis.

Rule 3: State governments are pass-throughs for formula funds, which become competitive locally

ARPA funds that will flow to states as formula grants may also be opened-up to municipalities or non-profits as competitive grants. City staff overseeing ARPA funds should familiarize themselves with how their state distributed supplemental funds received through federal formula grant programs in the CAREs Act and December 2020 Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act (CRRSAA) and should be in regular communication with state agencies about their plans for the distribution of supplemental ARPA funds, particularly state health and human services departments.

Example: The State of Pennsylvania received $55 million in COVID-19 supplemental funds from the CRRSAA for the Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment Block Grant Program. The state Department of Drug and Alcohol Programs awarded $2.7 million of those funds as competitive grants, worth up to $400,000 each, issued to five to eight organizations working to offer employment services to those in recovery from substance abuse. ARPA included an additional $1.5 billion in supplemental funds for the Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment Block Grant Program.

The Long Term: Strategizing for an Equitable Recovery

ARPA offers over $410 billion in funds that can be used to make long-term investments in broadband, economic and workforce development, clean water and sewer systems, affordable housing, public health infrastructure, small business growth, as well as the funds necessary to invest in systems-level changes to improve service delivery and build new opportunities for communities hit hardest by the pandemic.

While ARPA is focused on relief, some funds ––such as SSBCI, EDA grants, and HOME programs–– can be used for long-term investments in small business, sector-based development, and affordable housing. These recovery funds will move slowly and will be best leveraged by communities with strong collaborative networks and financial intermediaries. Local stakeholders should connect priority uses of flexible funds to eligible long-term, discrete program funds in order to maximize their impact; they should seek out private or philanthropic capital to ensure dollars are used to lay the groundwork for fiscally sustainable initiatives. Measuring investments for desired impact will only increase a city’s ability to attract outside matching funds.

Example: In Macon-Bibb County, Georgia, the Knight Foundation has pledged to double the county’s SLFRF investment in the creation of new affordable rental housing.

It bears repeating that flexible SLFRF funds have key restrictions around use and will expire after 4 years. Any new programs that are established are at risk of running into a fiscal cliff ––and potentially could create or worsen structural deficits–– after this time if they do not secure sustainable funding by FY26. As such, local decisionmakers should proceed with caution and careful thought. A chart summarizing long-term ARPA programs is here.

We are grateful for thorough, insightful, and detailed reviews from the City of Philadelphia’s Office of the Director of Finance and the City’s Office of the Controller. All remaining errors are our own.

Bruce Katz

Bruce is the Co-Founder and inaugural Director of the Nowak Metro Finance Lab.

Karyn Bruggeman

Karyn is a Research Officer at Drexel University's Nowak Metro Finance Lab. She has a background in policy research, journalism, and communications. Prior to this, Karyn worked for the State Innovation Exchange, and before that spent nearly four years reporting on politics and campaigns for National Journal. Karyn earned her B.A. from the College of William & Mary and an M.P.P. from the Harvard Kennedy School, where she focused on state and local government innovation and workforce policy.

Colin Higgins

Colin is a Senior Research Fellow at the Nowak Metro Finance Lab. He comes to this role with a background in policy research and implementation, previously working as program director at The Governance Project. Prior to this, Colin worked on a variety of environmental initiatives, campaigns, and economic policy in the Upper Midwest. Colin earned his B.A. and M.P.A from the University of Wisconsin – Madison and received his MPhil from Oxford University as a Rhodes Scholar.